By the end of last week, there was a shred of hope that the worst might be over for 2022's massive rate spike. By Tuesday of this week, however, that hope was shredded. Things only got worse from there.

To understand why, we have to revisit the general motivation for the rate spike. Before we do, let's put "massive" in context. It's not an overstatement considering this is the biggest, fastest jump in mortgage rates since at least 1994.

As for the "why," it's actually fairly straightforward. The Federal Reserve (aka "the Fed") is best known for setting the Fed Funds Rate which dictates the cost of the shortest term financing. It raises and lowers that rate to try to persuade inflation and employment to remain in certain ranges. In cases where the rate is cut to zero and the Fed thinks more needs to be done, they buy bonds (US Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities, specifically). Buying bonds creates excess demand in the bond market which in turn pushes longer-term rates lower. It's basically a way for the Fed to influence both short and long-term rates.

At the start of the pandemic, financial markets were in chaos and the Fed stepped in to cut rates to 0% and buy bonds at a faster pace than ever before. Rather than dial back those bond purchases when markets began to settle, the Fed concluded that it should continue providing as much monetary stimulus as possible in light of covid's impact on the labor market. They justified this with the assumption that covid-driven inflation would subside as the pandemic subsided.

As we now know, covid-related inflation didn't subside. By the Fed's own admission, it drastically miscalculated the persistence of inflation and even the health of the labor market. As 2022 approached, we suddenly found ourselves staring down the barrel of the biggest inflation numbers and the tightest labor market in decades. Meanwhile, the Fed still had its Fed Funds Rate at 0% and was still buying more than $100 billion in bonds each month.

Change was slow to come at first. In September 2021, the Fed began winding down new bond purchases--a process it needed to complete before hiking rates. A few months later, as inflation continued to surge and the labor market grew tighter, the Fed began accelerating its exit from easy money policies, but much like a battleship in a river.

By early 2022, the Fed's communications spoke to a certain level of panic not seen since the 80s. The Fed does not like to make big course corrections once it starts to turn the proverbial battleship, but 2022 has seen those sorts of unexpected accelerations one after another. This rapid rethink and rapid removal of bond buying demand on the part of the Fed is the key ingredient in the rate spike seen so far in 2022. This week merely brought the latest iteration.

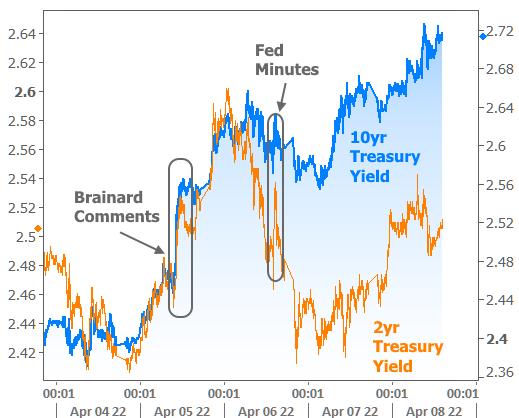

Specifically, in a prepared speech on Tuesday morning, Fed Vice Chair Lael Brainard (normally one of the most rate-friendly Fed speakers) joined a chorus of more hawkish Fed members who've been talking up the possibility of extremely large reductions in Fed bond buying (referred to as "normalization"). This wasn't an entirely new concept as the Fed is already on record saying 2022's normalization will definitely be bigger and faster than 2017--the only relevant precedent. That said, the market was surprised to hear it from Brainard--at least in such emphatic terms.

One of the reasons for the surprise was the fact that the following day would see the release of the Minutes from the most recent Fed meeting (3 weeks prior). Fed Minutes often contain additional clues about impending policy changes. Traders correctly assumed that there could be a bombshell in the current version. That went a long way toward softening the blow when the Minutes actually came out.

So what was all the fuss about?

In a nutshell, the Minutes laid out an explicit roadmap for normalization. Whereas the Fed rolled out 2017's normalization process with a $4 bln per month hit to MBS (mortgage-backed securities) purchases, 2022's plan calls for phase one to start at a staggering $35 bln per month! The discrepancy is similar when it comes to the Fed's Treasury purchases. Again, we knew it would be bigger and faster, but not quite this big/fast.

Because Fed bond buying targets longer term rates, that's where we saw the pain after the Minutes release. In other words, things like 10yr Treasury yields continued moving higher while 2yr Treasury yields managed to recover.

Mortgage rates care about 10yr yields because 10yr yields speak to trends in "longer-term rates" in general. Alternatively, forget all that and just observe the correlation in the following chart:

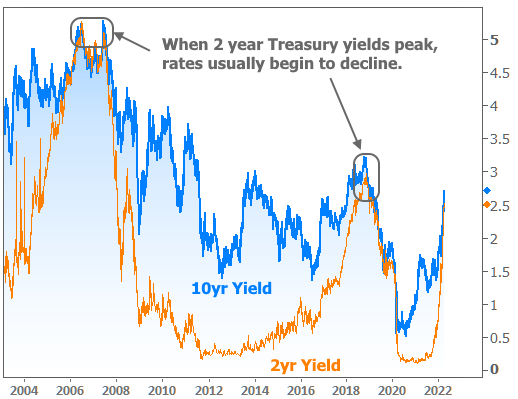

While longer term rates also correlate with shorter term rates, as you can see in the following charts, it's not quite the same. Short term rates rise and fall faster, and less often. Interestingly though, when short-term rates peak, relief typically isn't far behind for longer-term rates. Unfortunately, we have yet to confirm that peak.

So many things are so different about this economic/monetary cycle that past precedent may not be as useful as normal. All we really know at the moment is that we're waiting for several key developments. The most important among those would be for inflation data to show signs of shifting. That could take months though, and the bond market may have priced in an overabundance of caution by then.

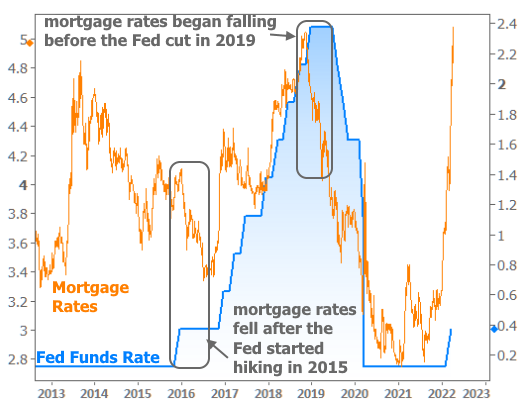

Before that, we're waiting to see what triggers the Fed actually pulls at its upcoming meeting in May. Certainly they'll be hiking, probably by 0.50%. They're also likely to enact the normalization plan laid out in this week's Minutes. If that's the extent of the damage, then the market will finally be on the same page with the Fed (barring any additional accelerations in the coming weeks). Paradoxically, that means the rate hike and big reduction in bond buying could actually be a good thing for longer term rates.

It wouldn't be the first time we've seen such a paradox. Longer term rates always do their best to account for future possibilities. If they know the Fed is likely to hike short term rates or to normalize bond purchases at a certain pace, they're free to move on to their next trend. In several past occasions, we've actually seen mortgage rates move lower while Fed policy was tight or tightening.

So again, the only question is: how well have long term rates priced in the future this time? It's only been the unexpected changes in the outlook that have caused so much extra upward momentum in rates. Once that outlook stabilizes, rates will probably already be coming back down. Unfortunately, there's no telling if that's the sort of thing that will happen in a few weeks, a few months, or in fits and starts throughout the year.