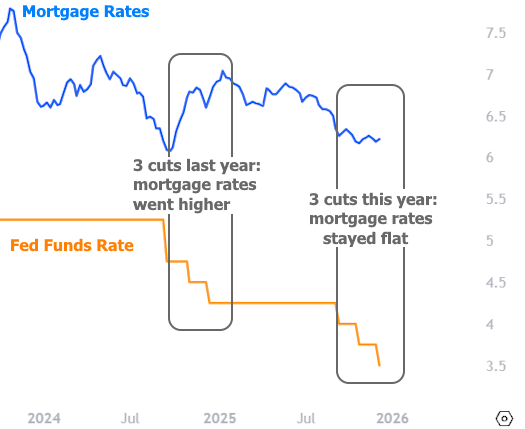

Friends don't let friends believe the myth that Fed rate cuts result in lower mortgage rates.

If you'd rather not immerse yourself in the "why," here is a solid "what:"

This isn't an anomaly. The Fed Funds Rate governs loans that last less than 24 hours whereas a mortgage can last 30 years. Loans of different durations frequently see their interest rates walk vastly different paths.

But even if we assume strong correlation, the Fed only meets 8 times a year, whereas mortgage rates move every day. That means the mortgage market will always be able to move in advance of the Fed as long as the market has a solid sense of what the Fed is going to do.

Transparent Fed comments and trading instruments like Fed Funds Futures mean the market has enjoyed high degrees of confidence regarding recent Fed cuts. Every cut in 2025 has been more than 90% likely in the days leading up to the Fed announcements. This week's was no exception. In fact, the market's reaction to the Fed fell well inside this week's trading range when it came to longer-term rates.

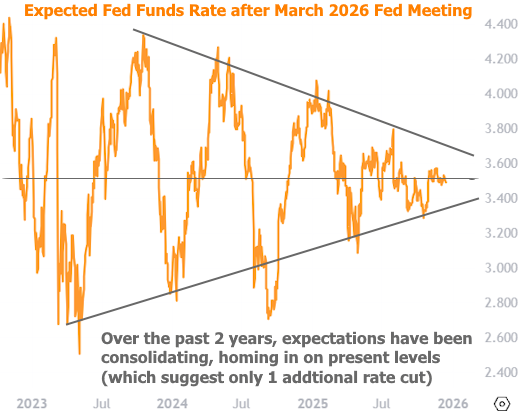

It doesn't hurt that the Fed's policy path is becoming increasingly locked in. As far as markets are concerned, we'll only see one more rate cut by early 2026. We've been homing in on this realization for several years, and especially over the past 3 months. NOTE: in the chart below, a value of 3.375 represents one additional cut from current levels.

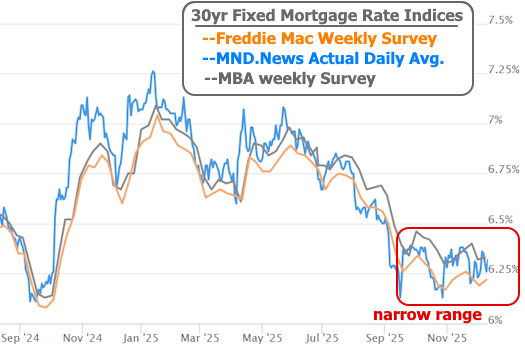

The increasingly narrow range of Fed rate expectations correlates with an increasingly narrow rate range, both for U.S. Treasuries:

and for mortgage rates:

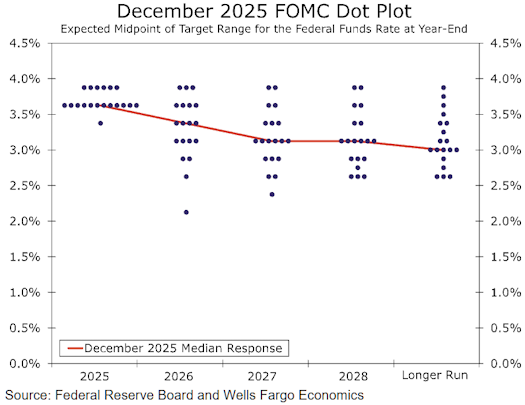

The Fed's own forecasts validate market expectations. At this week's meeting, the Fed updated its "dot plot" (a chart where the dots show each Fed member's rate expectation at the end of the next few years). Long story short, the median Fed member sees only one more cut in 2026, and then perhaps one more by the end of 2028.

What does this mean for you and for mortgage rates? Not too much. This is all retrospective at this point. The things that matter for rates have yet to happen. These include any major developments in economic data or fiscal policy.

On the data front, next Tuesday brings the much-anticipated release of the November jobs report (originally scheduled for last Friday, but delayed due to the shutdown). If the data suggests additional labor market weakness, another Fed rate cut becomes increasingly likely. Longer-term rates would move lower in anticipation, but could be subject to countervailing forces from other data.

For example, we're still waiting on timely inflation reports post-shutdown and next Thursday brings the delayed release of November's Consumer Price Index (CPI). If inflation is higher than expected, it could offset any rate-friendly impact from the jobs report.

And of course, either report could go in either direction. Think of it like 2 coin flips. If both are heads or tails, the movement in rates would likely be more forceful in a certain direction. If one is heads and the other is tails, they could cancel each other out.

A Final Note on Fed Bond Buying

There's a lot of confusion about the Fed announcing a shift in its bond buying plans this week. Some people are referring to it as QE (quantitative easing) and expecting it to push rates lower. Those people are wrong.

QE would involve an intentional oversupply of liquidity and reserves into the banking system with the intent of forcing institutions to lend money more aggressively even for longer-term loans, thereby putting downward pressure on long-term rates (like mortgages).

In contrast, this week's announcement was a widely-expected and well-telegraphed decision for the Fed to prevent further loss of liquidity. Reserve balances have been shrinking as institutions have been forced to bid on an ever-growing glut of short-term U.S. Treasury debt. If those reserves get too low, institutions will struggle to make loans and provide liquidity to the financial system, thus resulting in higher rates and episodes of excessive volatility.

To prevent this, the Fed will buy just enough short-term Treasuries to provide adequate liquidity/reserve balances in the financial system. Yes, this helps rates stay lower than they otherwise might go in the coming months, but no, it's not QE. More importantly, it was something the Fed was telling us would happen for more than a year, and something banks were--well... banking on. Bottom line: no one should expect this new bond buying to push rates lower. It's merely a safeguard against them going unnecessarily higher.